Table Of Contents

- Colt Python 357 Magnum

- 357 SIG vs 357 Magnum – WHICH OF THE TWO IS BETTER?

- 357 SIG vs 357 Magnum – THE TALE OF THE TAPE

- 357 SIG vs 357 Magnum - THE TALE OF THE TAPE

- 357 SIG vs 357 Magnum – AMMO AND FIREARMS PRICING

- Who Makes Guns Chambered in .357 Sig?

- CALIBER CONVERSIONS

- How to Choose Between – 357 SIG vs 357 Magnum

- 357 SIG vs 357 Magnum – CONCLUSION

- Recommended Reading

Before I go into the meat of my 357 SIG vs 357 Magnum article, I want to talk about my love for magnum revolvers.

Snake Guns

It’s official. Colt, after being tight-lipped about one of their biggest snake gun resurrection projects for the last five years, has finally unveiled what many consider to be their most respected revolver from what seemed like a lifetime ago: the Colt Python.

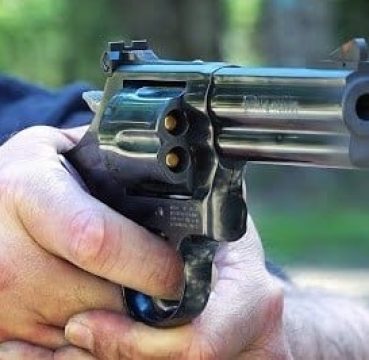

Colt Python 357 Magnum

Yes, I know the world of firearms has moved on. Gone are the days when magnum revolvers reigned as the supreme everyday carry handgun for civilians, law enforcers and medium game hunters, when high-capacity magazine-fed semi-autos were just a figment of some random gun nut’s imagination.

But this is the Colt Python, a legendary revolver that has been dead for a long time. We all thought it would never be brought back to life! But I digress.

Let the 357 SIG vs 357 Magnum Debate Begin

Recently, one of our readers (let’s call him Bob) emailed me with a rather commonly asked question on a much debated topic, one I usually shy away from because there are just too many arguments surrounding it (and I’m sure a few of our wheelgun-loving regulars know of my biases as far as handgun calibers is concerned)…

357 SIG vs 357 Magnum – WHICH OF THE TWO IS BETTER?

Bob didn’t sound like the type who’s into debates. The only reason he had to ask was, for the longest time, he has been thinking of getting a revolver in .357 Magnum. But he has yet to make up his mind on whether or not he should get one, because he’s already got a Glock 31.

That, and some people on the Internet say that the .357 SIG, being it was made to duplicate the ballistics of the .357 Magnum, is as powerful, if not more. I’ve personally read an article written by an expert gunsmith claiming that the .357 Sig can be even more powerful than the .357 Magnum (I have great respect for the guy and his works — very few people can do revolver customization the way he does — but his claim is a hard pill to swallow).

But the aforementioned Colt Python’s resurrection got him a bit interested again — he’s just not 100% convinced that he needs one just yet (and news of current production Pythons having issues with the cylinder clockwork isn’t making things easy for him too).

If you’re like Bob (and I’m sure some of you are), that is, you’re looking to get a revolver chambered for the .357 Magnum but you’re not sure whether you should because you already have a handgun in .357 SIG, or you simply just want to know whether one is better than the other for whatever purpose you might have, read on.

THE .38 SUPER: WHAT REALLY STARTED IT ALL

When Colt released a 1911-style pistol chambered in 1929 for what was then the most powerful handgun cartridge in the world — the .38 Super Automatic — Smith & Wesson decided to do something similar but took an entirely different approach.

A year after, they manufactured new N-frame revolvers (originally built for their .44 Special) and chambered those for their .38 Special, labeling them the .38-44 Heavy Duty revolver.

This platform showed promise, but a growing community of individuals passionate about the .38 Special knew that the .38 Special was capable of so much more. Two of them, Phil Sharpe and Elmer Keith, set out to develop their own hot-loaded versions of the.38 Special.

.38 Super the Early Days

From the late 1920s to early 1930s, the two gentlemen experimented with various bullet and powder types and weights, little by little pushing the .38 Special cartridge case well beyond its established pressure limits.

Keith’s efforts proved that the .38-44 Heavy Duty and Outdoorsman N-frame revolvers could safely chamber and shoot much more powerful .38 Special cartridges than the ones Remington manufactured.

Keith’s creation had to get the nod from Smith & Wesson and Remington for it to go mainstream. He eventually lost interest as he had his eyes set on the cartridge the Heavy Duty and Outdoorsman N-frame revolvers were originally chambered for, one that had even more potential as far as ballistic performance and would one day easily surpass his .38 Special hot load: the .44 Special.

Meanwhile, Phil Sharpe continued with his own hot loads development. He would eventually work closely with Col. Dan B. Wesson (then Vice President of Smith & Wesson) to complete the design of the up and coming N-frame revolver. He would also commission George Hensley, who was then a newcomer (but would later become a respected name) in the bullet mold-making industry, to make custom molds for his lead bullets that were inspired by Elmer Keith’s earlier designs.

THE RISE AND FALL OF THE .357 MAGNUM

This new shooting platform instantly dethroned Colt’s 1911 in .38 Super and became the most powerful handgun in the world, as Sharpe’s 160-grain solid bullets were reportedly able to achieve previously unheard of velocities of anywhere between 1,500 and 1,600 feet per second out of a revolver.

The Model 27 became an overnight success, even with its initial unrealistically high price with both law enforcement and civilians. Not too long after, many different .357 Magnum loads were being developed by ammo manufacturers — loads that were noticeably becoming weaker compared to Keith’s and Sharpe’s original loads but were still more than good enough for law enforcement use.

Then Came the Semi-Autos

All was well and good in the world of wheel guns from 1935 up to the early 1970s when a new breed of handguns would usher in a new era. These handguns were chambered in 9mm Parabellum, used staggered-column magazines that allowed for higher ammo capacity compared to standard semi-autos of old, and could be fired without having to rack the slide.

The End of the Revolver’s Dominance

Today these 9mm handguns have become the de facto standard in law enforcement sidearms, but back in the days, they were affectionately referred to as the Wonder Nines. These guns changed the landscape, practically pushing the concept of law enforcement revolver use to obsolescence.

Because of this, the .357 Magnum revolver platform lost its dominant position in the law enforcement scene. Currently, civilians still prefer it over any other handgun for home defense (mainly as a nightstand gun), as a truck gun, trail gun, tackle box gun, or as a backup gun when hunting dangerous game. But it’s nowhere near as great as it used to be.

THE ADVENT OF THE 10MM AUTO

As mentioned earlier, in the late 1960’s, 9mm handgun models with staggered-column magazines were starting to creep their way into the police and civilian markets which were then largely dominated by the 1911 chambered in either .45 ACP or .38 Super and six-shot revolvers chambered in .357 Magnum.

The 9mm cartridge wasn’t anywhere near as common or as popular as it is now. Compared to its early contemporaries, its ballistic performance was significantly weaker. It would have fallen by the wayside (like most other weak calibers that came before it) if it weren’t for the one thing all 9mm-chambered handguns are good for: a high round-count magazine.

This presented a problem: law enforcement and civilians wanted the high capacity magazines 9mm handguns offered. But they couldn’t let go of the sheer ballistic performance advantages presented by .45 ACP 1911s (which typically have an 8+1 mag capacity) or .357 Magnum revolvers (which usually only hold six rounds).

Two businessmen, Thomas Dornaus and Michael Dixon, saw this as an opportunity to make a name for themselves by building what they conceived as the ultimate handgun — one that could surpass the .45 ACP (and even the .357 Magnum) in energy levels but could give the Wonder Nines a run for their money in the ammo capacity department.

Having no prior experience as far as developing hot loads for existing handgun cartridges, they asked for expert advice on the subject. In came former U.S. marine and handguns expert Lt. Col. John Dean “Jeff” Cooper.

Jeff Copper’s .45 ACP

The idea of the 10mm cartridge was originally conceived by Jeff Cooper, himself a .45 ACP purist, in 1983. It centered around a cartridge that would outperform the .45 ACP using a 200-grain, .40-caliber bullet seated in a straight-walled rimless cartridge for use in a semi-automatic pistol with a nominal 5-inch barrel. The target velocity was at least 1,200 feet per second. But no handgun at the time could handle such a powerful cartridge.

The three collaborated, with the two businessmen on the engineering side of things and the handguns expert acting as an independent consultant. Their efforts led to the creation of the Bren Ten handgun. Afterward, they went to Sierra to make .40-inch diameter 200-grain bullets and had John Donnelly (a friend of Jeff Cooper’s) handload the first 100 cartridges using those bullets.

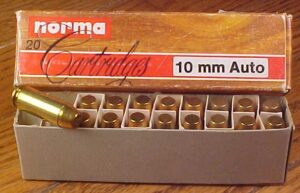

The businessmen needed the ammo mass-produced so they approached a few ammunition makers but were turned down by every single one of them — except by FFV Norma AB (now Norma Precision), a Swedish ammunition manufacturer. Later that same year, Norma Precision started producing the 10mm.

Norma’s 10mm version was a little on the hotter side, with velocities slightly exceeding Jeff Cooper’s (i.e. by around 60 feet per second). Michael Dixon christened it the 10mm Auto, but the purists refer to it as the 10mm Norma.

THE BIRTH OF THE .357 SIG

In 1986, the FBI included the 10mm Auto in their handgun ammo tests as a possible replacement for their then standard issue 9mm after two of their agents were killed and a few others were severely wounded during what is today considered one of the bloodiest armed confrontations in the history of law enforcement: the Miami Dade Shootout.

This event pushed many ammo manufacturers to produce 10mm FBI loads (or “10mm Lite” as older folks call it). Ultimately this would result in Smith and Wesson developing the .40 S&W in 1989, the “short and weak” offspring of the 10mm that would ironically cast a shadow over its more powerful parent cartridge. The 10mm would then fade to near obsolescence.

How the .357 Sig Came to Be

Not too long after, SIG Sauer, at the time an emerging leader in handguns manufacture and design (thanks to their entry that passed the highly controversial XM9 and XM10 Trials, the SIG P226), did their own version of the .40 S&W, except after cutting down the 10mm’s brass, they necked it down to accept a .355-caliber projectile. They called this cartridge the .357 SIG — an homage to the revolver caliber whose ballistics it attempts to mimic.

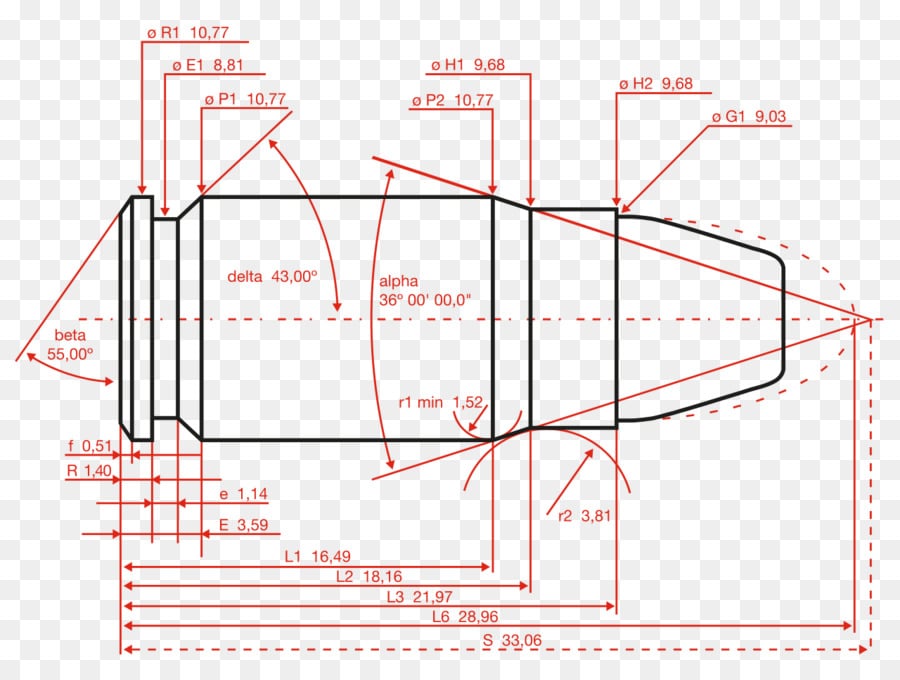

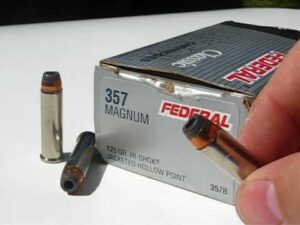

Not much is known about the .357 SIG’s early development except that it was a result of a collaboration between SIG Sauer and Federal. It was created specifically for the SIG P229 with the necked-down brass having more than enough strength to handle the pressure levels generated by duplicating the ballistics of Federal’s 125-grain .357 Magnum load.

As it was designed to be a semi-auto cartridge, the .357 SIG shooting platform proposes numerous advantages over its magnum revolver counterpart, some of which are:

What are the Advantages of the .357 SIG?

- Modern semi-auto handguns usually have more than double the ammo capacity of conventional revolvers;

- There is no forcing cone velocity loss in a semi-auto because it doesn’t have a forcing one. Unlike a revolver’s barrel that is separate from the multiple chambers in its rotating cylinder, a semi-auto’s barrel and chamber are machined from a single piece of metal. This means there is no gap between the semi-auto’s chamber and barrel.

- Unless you’re Jerry Miculek, magazine-fed handguns are typically faster to reload than revolvers;

- By virtue of its flat profile, a semi-auto doesn’t require too much effort to carry concealed, The revolver’s cylinder on the other hand has a bulging profile that easily prints, making it a bit harder to conceal.

Faster Draw?

- It’s much faster to draw a semi-auto handgun from an IWB holster because its flat surface won’t snag clothing. A revolver’s hammer spur can be cut so it can be drawn faster without snagging clothing as well, but doing so will make it DAO. Some people are okay with that. Personally, if I want to carry a DAO handgun, I’d go with a Beretta 92D.

- A semi-auto handgun by design has a recoil spring that utilizes some of the force of the recoil (i.e. to eject the spent case and snag a fresh cartridge from the magazine’s lip). When comparing two similar-weight guns shooting cartridges with similar ballistics, if one is a semi-auto and the other is a revolver, the semi-auto will have noticeably less recoil, giving it a speed advantage as far as target acquisition and follow-up shots.

Because of the platform’s advantages, the P229 chambered for .357 SIG was adopted as the standard issue sidearm (and is still in use today) by many different federal government and law enforcement agencies, some of which are: Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), Customs and Border Protection (CBP), Federal Protection Service (FPS), Federal Air Marshal Service (FAMS). U.S. Secret Service (USSS) and U.S. Coast Guard (USCG). But strangely, the caliber never caught on in the civilian market in terms of popularity.

357 SIG vs 357 Magnum – THE TALE OF THE TAPE

For anyone who had to skip the history section for some reason, the most important takeaway from it is that the .357 SIG was an attempt to duplicate the ballistic performance of one particular .357 Magnum load: Federal’s 125-grain jacketed hollow point fired out of a revolver with a four-inch barrel. Whether or not it’s a successful attempt depends on one’s definition of success.

How do we define success? Let’s take a look at the 357 SIG vs 357 Magnum chart below. It looks rather boring but we’ll need it to see the bigger picture later on:

357 SIG vs 357 Magnum - THE TALE OF THE TAPE

| .357 Sig | Cartridge Specs | .357 Magnum |

|---|---|---|

| 0.355 | Bullet diameter (in) | 0.357 |

| 0.381 | Case neck diameter (in) | 0.379 |

| 0.424 | Case base diameter (in) | 0.379 |

| 0.865 | Case length (in) | 1.29 |

| 125 | Early bullet weight (gr) | 160 |

| 180 | Heaviest factory ammo bullet weight (gr) | 200 |

| 1450 | Early velocity (fps) | 1600 |

| 1050 | Heaviest bullet velocity (fps) | 1300 |

| 583 | Early muzzle energy (ft. lbf) | 909 |

| 441 | Heaviest bullet muzzle energy (ft. lbf) | 750 |

| 40,000 | SAAMI pressure rating (psi) | 35,000 |

Here are a few things to note:

- The .357 SIG was originally designed to have enough power to propel a 125-grain .355-inch diameter jacketed hollow point bullet out of a 4-inch barrel at a velocity of 1,450 feet per second. These numbers produce a muzzle energy of around 583 foot-pounds of force.

- The original Phil Sharpe loading for the .357 Magnum called for a 160-grain .357-inch diameter hard cast lead bullet. Out of a 6-inch barrel, the bullet flies at a velocity of 1,600 feet per second, producing a muzzle energy of around 909 foot-pounds of force. This is 326 foot-pounds in excess of the original .357 SIG load’s muzzle energy, or a difference of 55.91% in favor of the .357 Magnum.

- Back to the .357 SIG, the heaviest bullet commercially available at the moment is Double Tap’s 180-grain Hardcast Solid. It has an advertised velocity 1,050 and will produce a muzzle energy of 441 foot-pounds of force.

What is the Heaviest Bullet in .357 Magnum?

The heaviest bullet available on any factory .357 Magnum loading is a hard cast lead wide flat nose that weighs 200 grains. The ammo is manufactured by Grizzly Cartridge Company and has an advertised velocity of 1,300 feet per second that will result in a muzzle energy of 750 foot-pounds of force. This is 309 foot-pounds greater than Double Tap’s .357 SIG Hardcast Solid, or a difference of 70.06% in favor, again, of the .357 Magnum.

- Some people like to factor in ammo capacity when trying to ascertain the destructive capabilities of a particular firearm. Just so we have this area covered, the .357 SIG handgun with the highest round count is a Glock 31 with a 15-round mag. Its counterpart could be any N-Frame size revolver (e.g. S&W TRR8 or Ruger Redhawk Model 5060) that will hold up to eight rounds of .357 Magnum.

- Fifteen rounds of 125-grain .357 SIG will generate a total of 8,745 foot-pounds of force, while eight rounds of Phil Sharpe’s original .357 Magnum load will produce a total of 7,272 foot-pounds of force. This is a difference of 1,473 foot-pounds of force favoring the .357 SIG which amounts to 20.25% more energy, but keep in mind that you need 15 rounds or 87.50% more ammo to achieve this.

OTHER MISCELLANEOUS TECHNICAL INFO

Unlike the .357 Magnum, the .357 SIG’s bullet diameter doesn’t exactly measure three-hundred fifty-seven thousandths of an inch. It’s around two thousandths of an inch narrower, which means if you’re planning to reload, a bullet meant for the .357 magnum will not fit in a 357 SIG case.

Bullets for the .357 SIG are of the same diameter as those for the plentiful 9mm Parabellum. But this doesn’t automatically mean any bullet intended for 9mm brass can be used for .357 SIG when reloading. You can use full-metal jacket and hard cast lead bullets, but not jacketed hollow points. Why, you ask?

Jacketed hollow point 9mm bullets will expand much sooner than expected when fired from .357 SIG brass, resulting in less penetration. Bonded jacketed hollow point bullets will also exhibit core-jacket separation. This is because the .357 SIG will push a 9mm Parabellum bullet much faster and with more energy, changing its terminal performance for the worse.

Not to belabor the previous point, but no matter how plentiful 9mm bullets could be, 357 SIG ammo for self defense can’t be manufactured cheaply because as mentioned, the caliber requires its own uniquely manufactured bonded jacketed hollow points. This is one of the reasons why .357 SIG factory ammo is more expensive compared to its weaker 9mm brethren, which brings us to everyone’s favorite topic: Price.

357 SIG vs 357 Magnum – AMMO AND FIREARMS PRICING

This isn’t a Top 10 type of post so we’re not comparing guns on their mechanical merits and disadvantages. We’ll only include some of them here to give an idea on pricing. Here’s a quick list of 357 SIG vs 357 Magnum:

| Caliber | Brand | Model | Price |

| .357 SIG | SIG Sauer | P226 | $$$ |

| .357 SIG | Glock | G31 | $499.99 |

| .357 SIG | SIG Sauer | P229 | $1,199.99 |

| .357 SIG | Glock | G32 | $539.99 |

| .357 SIG | SIG Sauer | P320 | $579.99 |

| .357 Magnum | Colt | Python | $1,632.99 |

| .357 Magnum | Dan Wesson | Model 715 | $1,539.99 |

| .357 Magnum | Smith & Wesson | Model 686 | $749.99 |

| .357 Magnum | Ruger | GP100 | $689.99 |

| 357 Magnum | Taurus | Model 692 | $499.99 |

It’s interesting to note that both the cheapest and the most expensive guns on the list are chambered in the .357 Magnum (the Glock 31 is currently priced the same as the Taurus 692 but the latter’s street price is typically much lower than what it retails for). And the chart doesn’t show it, but there are far more .357 Magnum revolvers than there are handguns chambered for the .357 SIG.

Who Makes Guns Chambered in .357 Sig?

That’s because there are really only two companies making guns chambered for the .357 SIG: Glock and SIG Sauer, with the former being the cheaper option all the time. By comparison, there are countless companies manufacturing revolvers (take a look at this other article I wrote if you want to know what options are available to you) and lever-action rifles chambered for the .357 Magnum. And don’t even get me started on the Coonan 1911-style handgun.

But we won’t recommend that you make a decision based on firearms pricing — especially if you intend to visit the range often, in which case you should prioritize ammo cost over anything. Here’s probably the most important 357 SIG vs 357 Magnum chart in this article that you’d want to look at:

Ammo Choices for 357 SIG vs 357 Magnum

| Caliber | Brand | Bullet Wt. | Velocity | Muzzle energy | Price per box |

Per-round price

|

| .357 SIG | CCI Speer Lawman TMJ | 125 | 1325 | 487 | ||

| .357 SIG | Winchester White Box JHP | 125 | 1350 | 506 | ||

| .357 SIG | Double Tap Hardcast Solid | 180 | 1025 | 420 | ||

| .357 Magnum | Remington UMC | 125 | 1450 | 583 | ||

| .357 Magnum | Fiocchi Shooting Dynamics SJSP | 125 | 1500 | 624 | $18.08 | $0.36 |

| 357 Magnum | Double Tap | 195 | 1145 | 568 | $14.99 | $0.75 |

We’re including three different brands of ammo for each caliber, each representing three different budget segments. Rows 2 and 5 represent the cheapest ammo for practice drills; rows 3 and 6 represent the most affordable carry ammo for your CCW; and rows 4 and 7 represent the hottest commercially produced loads on the market that you can use for hunting up to medium-size game, e.g. whitetail and hog.

From the chart above you can see that while the .357 Magnum offerings have higher muzzle energies compared to their .357 SIG counterparts, they’re also a lot cheaper. This makes the .357 Magnum more affordable, more accessible, and consequently more versatile than the .357 SIG as a shooting platform. And speaking of versatility…

CALIBER CONVERSIONS

Both platforms allow for a dual-caliber setup, but one is more expensive than the other. All .357 SIG handguns can be converted to shoot .40 S&W, its sister caliber, but it will require a barrel swap (and sometimes the recoil spring has to be changed too for 100% reliability).

Similarly, all .357 Magnum revolvers will shoot .38 Special out of the box, with one exception: the M47 Medusa.

Released in 1993, the M47 Medusa has a unique cylinder with chambers that can load a hundred different handgun and revolver calibers, i.e. those with bullets measuring anywhere from .355 inch to .357 inch in diameter. But it’s one odd duck in the revolver world that very few cared about so after making five hundred pieces, the manufacturer had to discontinue production. There’s a silver lining though.

Multi-caliber .357 Magnum revolvers have been seeing a resurgence in the past couple of years, i.e. wheelguns that come with two cylinders out of the box: one for .357 Magnum/.38 Special, another for 9mm Parabellum. There’s Korth’s Super Sport, Ruger’s Blackhawk Convertible and Taurus’ Model 692 to name a few. So as far as versatility, the .357 Magnum wins.

How to Choose Between – 357 SIG vs 357 Magnum

If you’re on the fence whether or not you should spend your hard-earned dollar on a gun chambered for a specific caliber, the best piece of advice we can give you is to determine your purpose. Both calibers and their shooting platforms have their fair share of strengths and weaknesses. But what it all boils down to is what you’re going to purchase a gun for.

Handguns for the .357 SIG are mainly for law enforcement and concealed carry in urban environments but can be called upon in a pinch if you’re out hunting and your main rifle fails and you really need something to defend yourself with against things like black bear (it has to be said though: I would only recommend the .357 SIG for that purpose if you don’t have a more powerful handgun for backup).

Revolvers chambered for the .357 Magnum come in all shapes and sizes. Small-frame revolvers can be easily concealed while medium frames can be a challenge. And unless it’s rainy season, it’ll be near impossible to carry a large-frame revolver on your person without it printing.

Which is Better for Concealed Carry – 357 SIG vs 357 Magnum?

But if you’re in an environment where concealment isn’t required and you need superior firepower in the smallest possible package, a .357 Magnum revolver with a long enough barrel and loaded with the right ammo for the job is the bee’s knees.

This platform works so well that the French Spec Ops of the 1970s outfitted some of their Manurhin service revolvers with a tripod and scope for use as a sub-100-yard sniper rifle replacement. If you’re not convinced, here’s a video of a lowly Taurus Tracker taking antelope at over 130 yards:

357 SIG vs 357 Magnum – CONCLUSION

As far as we’re concerned, the .357 SIG only beats the .357 Magnum in one area: ammo capacity. Guns chambered for the .357 SIG typically have room for up to twice the number of rounds in a single reload. But that’s it.

Comparing ballistic performance, versatility, firearms and ammo availability and pricing, the .357 Magnum reigns supreme over the .357 SIG and many other handgun calibers on both the civilian and law enforcement market today. It has something for everyone, even those who hate revolvers.

Yes, you read that right. If you don’t like revolvers but you want to shoot full-power 357 Magnum rounds, you can get a Coonan pistol. Better yet, get a lever-action rifle in that caliber. As for me, all things considered, the winner of this Handgun Caliber Showdown is the .357 Magnum. And it’s a well-deserved win for this old-timer too.