How well do we know our Magnums?

Just a few days ago my wife’s relatives had a big family reunion. One of her uncles whom I’ve never met before overheard me and my wife talk about guns and as it turned out, he’s into guns himself.

The guy turns out to be a martial artist, bladed weapons collector and retired police officer — a real piece of work. He only just two years ago took an interest in firearms, and recently in rifles chambered for rimfire cartridges. We were talking about these when he asked for my opinion.

A question of 22 LR vs. 22 Magnum

He has an Armscor M1500, a bolt-action rifle chambered in .22 magnum that he purchased a few months ago. He loves shooting it but ammo is becoming more and more expensive and harder to come by. And rimfire ammo generally being near impossible to handload isn’t making things any easier.

He heard from his buddies that .22 LR ammo is dirt cheap and it got him interested in purchasing a rifle chambered in that cartridge. He’s going to shoot varmints and small edible game (mostly squirrels and prairie dogs) — but he also wants to take down coyote if he happens upon some, and for that purpose, he’s not sure whether the .22 LR would be as good as the .22 magnum.

What I Knew about Centerfire Cartridges:

Prior to doing this research, these were the only things I knew about rimfire cartridges:

- CCI is the most popular brand of rimfire cartridges.

- The cheapest ammo available for any type of caliber is .22 LR bulk ammo, which makes it the perfect practice and plinking round.

- Any bullet fired from a rifle will be significantly more powerful than when fired from a handgun. The rimfires are no exception.

- The .22 Magnum, being a cartridge that follows the “magnum” naming convention, has longer brass with room for more powder, which makes it more powerful than the .22 LR. Just how powerful though?

Everyone has, at one point, held and shot a rifle chambered for the .22 LR as their first firearm. And just like everyone, the things I know about the .22 LR are all in the realm of common knowledge. If I would opine on his issue, I would need to do some serious research.

Is there a difference between 22 LR vs. 22 Magnum?

Yes, there is a difference between 22 LR and 22 Magnum. 22 LR is a rimfire caliber that offers low recoil and is a great choice for casual target shooting and small game hunting. 22 Magnum, also known as 22 WMR, is a centerfire caliber with more power and range than 22 LR, making it a better choice for hunting small game and varmints.

In this cartridge showdown, we’ll attempt to determine whether the differences between the .22 LR vs. .22 magnum — two of the oldest surviving rimfire cartridges all over the world — are significant enough to choose one over the other (and hopefully help my wife’s uncle in the process).

Unpack This Article's Arsenal

- How well do we know our Magnums?

- A question of 22 LR vs. 22 Magnum

- Is there a difference between 22 LR vs. 22 Magnum?

- History of the Rimfire Cartridge

- History of The .22 Long Rifle

- The History of the .22 Magnum

- The Power of the .22 Magnum

- 22 LR vs. 22 Magnum – Barrel Ballistics

- 22 LR vs. 22 Magnum – Beyond the Ballistics

- Why is the .22 LR so Popular?

- 22 LR vs. 22 Magnum Pricing Comparison

- Best 22LR Ammo for the Money

- CCI Blazer – 22 LR – 40gr

- Best 22 Magnum Ammo for the Money

- CCI Maxi-Mag – 22 Magnum – 40 Grain

- Which is Better – 22 LR vs. 22 Magnum?

- 22 LR vs. 22 Magnum – Conclusion

- Recommended Reading

Get Great Guns And Ammo Deals!

SAFEST NEWSLETTER - WE WILL NEVER SELL YOUR EMAIL

No Spam - No Selling Your Email

History of the Rimfire Cartridge

To really get down to the nitty-gritty of the 22 LR vs. 22 Magnum comparison, let’s briefly take a look at each of these rimfire cartridges’ history.

22LR History

The .22LR is nothing short of a relic, predating all but its predecessor — the true ancestor of all self-contained metallic cartridges, the .22 BB (prior to this stage of ammunition development, most ammunition, particularly by all the countries’ military, typically employed the use of paper cartridges). The more common term for these cartridges among enthusiasts is the Flobert.

What is a Flobert?

A Flobert is a type of single-shot, rimfire, muzzle-loading firearm. It was originally designed as a training weapon for military personnel, but became popular among civilians as a target gun.

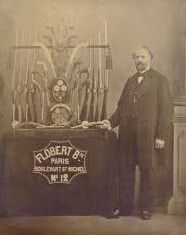

Most people would say the Flobert started out early on as some odd saloon cartridge invented only for smooth bore rifles by an enterprising French gentleman named Louis-Nicolas Flobert (hence the name of the cartridge), but older history books tell a different story.

During the black powder era some time in 1845, an inventor (who also happened to be another Frechman) by the name of Bernard Houllier invented a self-contained metallic cartridge that used what was essentially a percussion cap modified to have a folded hollow rim where the detonating powder can be packed.

Bernard Houllier’s Rimfire Design

Houllier designed the cartridge such that the powder was ignited when the hammer rammed the rim of the cartridge against the edge of the breech. He then stuck a tiny five millimeter bullet in front, and the first rimfire cartridge was born. He patented the design the next year.

.22 BBs

The early .22 BB (and even modern ones — they still exist as of this writing) are ballistically inferior to any other self-contained metallic cartridge, rimfire or otherwise, with the bullet weighing between 18 and 20 grains and having a muzzle velocity of 750 to 780 feet per second.

These numbers resulted in muzzle energies of anywhere between 20 and 26 foot-pounds of force, making the .22 BB useless in any kind of scenario requiring use of a firearm except indoor target shooting. For all intents and purposes, it was just another toy for the big boys.

But because of paper cartridges slowly becoming obsolete and self-contained rimfire cartridges gaining popularity among civilians, several ammunition manufacturers started redesigning the .22 BB to come up with their own more powerful version, gradually stretching the casing every time to allow for more and more powder.

Americans see Rimfire for the First Time

Louis-Nicolas Flobert brought all the guns he designed to the 1851 London Exposition, and it was here that two American firearm pioneers Horace Smith & Daniel Baird Wesson saw the rimfire cartridge for the first time.

History of The .22 Long Rifle

Inspired by its design, the two invented the first American metallic cartridge: the .22 (which would later be called the .22 Short), manufactured for the very first Smith & Wesson revolver in 1857, the Model 1.

Not long after, several different rifles were being chambered for it. It became popular but it was still ballistically weak, only managing around ~45 foot-pounds of force at the muzzle. This cartridge is still with us today.

When was the 22 LR invented?

Around 1880, the .22 Extra Long came out. It used a longer case than the .22 Long and a heavier bullet that was also unique in that it had a tapered heel. The longer case allowed for just a bit more powder which pushed the heavier bullet with the same velocity as the .22 Long’s. This resulted in around ~98 foot pounds of force at the muzzle.

The 22 LR is born

Less than half a decade after Flobert popularized Houllier’s rimfire cartridge concept, another .22 rimfire cartridge was developed. In 1887, the fine folks at Steven Arms Co. endeavored to create what was ballistically a .22 Extra Long in a shorter case — it loaded the same tapered heel bullet in the .22 Long’s shorter case.

The result was the .22 Long Rifle, a cartridge capable of propelling a 40-grain projectile at velocities of up to 1,050 feet per second, generating ~98 foot-pounds of force at the muzzle. It would later eclipse both its parent cartridges in both ballistic performance and popularity.

The History of the .22 Magnum

In 1890, Winchester introduced their first .22-caliber rimfire cartridge, the .22 Winchester Rimfire (.22 WRF). It used the typical full-diameter heel bullet, not the tapered heel bullet the .22 LR used. Remington called their version of this same cartridge the .22 Remington Special. These two are ballistically the same, only difference is Winchester’s used a flat point bullet while Remington’s used a round nose. Either will chamber in the same firearm no issues.

The 22 WRF

That significant increase in velocity, along with the .22 LR’s reputation for better accuracy, already cheaper price and the very high number of firearms chambered in .22 LR at the time, all contributed to the .22 WRF’s demise. But it didn’t die in vain.

The Death of the WRF Spawns the .22 Magnum

In as much the same way that the .38 Special gave birth to the .357 Magnum, the .22 Winchester Rimfire’s failure resulted in the conception of .22 Winchester Magnum Rimfire (.22 WMR), the round we now commonly refer to as “.22 Magnum”.

It was 1959 when Winchester introduced the .22 Magnum. As with all other attempts at improving over Houllier’s original rimfire cartridge design, the goal was simple: lengthen the case of the parent cartridge and add more powder.

Winchester pushes the limits of the 22.

But with the advent of smokeless powder, Winchester pushed the rimfire design’s pressure limits, making it so that a 40-grain projectile can be propelled at velocities approaching 2,000 feet per second and generating around ~350 foot-pounds of force out of a rifle barrel.

These ballistic numbers put the .22 Magnum in a higher caliber weight class (i.e. that of the 9mm out of a five-inch barrel), outclassing even the most powerful .22 LR hyper velocity loads from CCI by a factor of two when shot from a rifle. It has been 70 years since its inception but the .22 Magnum is still the most powerful .22-caliber rimfire cartridge to this day.

The Power of the .22 Magnum

The takeaway from all the history bit we’ve just gone through is the undeniable (but unsurprising) fact that like all magnum versions of their predecessors, the .22 Magnum is ballistically superior to the .22 LR.

Now there are a few places online where people bring up the barrel length argument — that is, they’re saying the .22 Magnum loses much of its velocity advantage over the .22 LR when both are fired from a handgun and even more so when both are fired from a snub nose revolver, making the supposedly more potent cartridge kind of pointless.

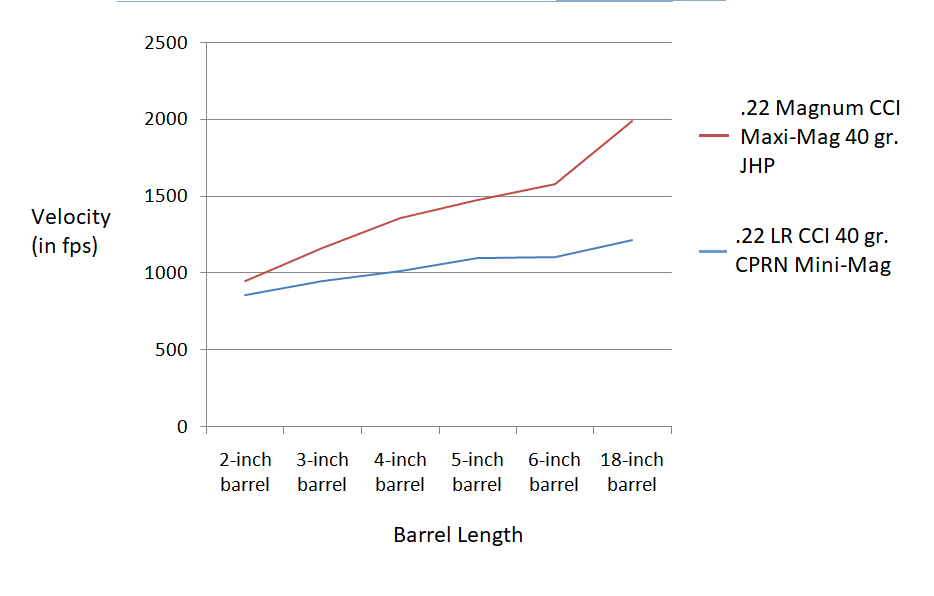

22 LR vs. 22 Magnum – Barrel Ballistics

The latter part of the claim is true, as can be quickly surmised by just checking velocity data from Ballistics By The Inch. Any gun that has a barrel measuring only two inches won’t have enough room to make use of the .22 Magnum’s powder. The story changes though if the gun in question has a barrel length of three inches or longer.

22 Magnum is netter for Longer Barrels

From the graph above, it can be seen that the gap between the red and blue lines significantly widens after the three-inch barrel mark, which means the .22 Magnum can make use of longer barrel lengths better than the .22 LR.

Another interesting thing to note is that there’s a .22 Magnum load developed by Speer specifically for shorter barrel handguns. It boasts good expansion and penetration out of something really tiny like a North American Arms Black Widow.

22 LR vs. 22 Magnum – Beyond the Ballistics

But the ballistic performance advantage the .22 Magnum has over the .22 LR doesn’t mean it’s winning. For all you .22 Magnum fans out there, I’m sorry to break it to you but here at Gun News Daily, we tend to look past ballistics when comparing cartridges to consider other similarly important things like price, availability and popularity.

Most firearms history books tell us that the .22 LR has become the most popular sporting and target shooting cartridge in the world, and that’s even after the .22 Magnum came out. How and why that happened, that’s anybody’s guess. Seriously, you can talk to different people and they’ll tell you all sorts of different things.

Why is the .22 LR so Popular?

The .22 LR is the most popular caliber in the world because of its versatility and affordability. It is a great choice for target shooting, small game hunting, plinking, and self-defense. It is a low-recoiling round that is easy to shoot and provides minimal felt recoil. It is also inexpensive to shoot, making it a great option for practice and training.

Additionally, its wide variety of ammunition types and sizes makes it a great choice for many different firearms applications.

Gathering all the available data I could find online, here are some of the biggest reasons why the .22 LR has become so popular and widely available:

- The cartridge has been around for a while that mass production of ammo has become so quick and cost-efficient, which is why some .22 LR ammo can be sold dirt-cheap to begin with.

- Being a tiny cartridge, there’s less of everything (i.e. brass, lead, powder) needed that makes all other cartridges more expensive to manufacture.

- Being relatively weak and unintimidating (to the point it can be considered gentle), it has become the newbie’s cartridge, and more and more young people getting into guns means steady demand.

- Guns chambered for the .22 LR are cheap and plentiful, and the high number of sales of these guns generate more demand.

22LR Hyper Velocity

Nevermind that modern .22 LR hyper velocity rounds are getting close to .380 ACP ballistics territory, or that some of the most accurate firearms ever built (for use in shooting competitions like those in the Olympics) are chambered for it, or that owning a .22 LR rifle is legal even in countries where owning firearms is supposed to be illegal because it’s so weak and pathetic that people think it’s a harmless little cutesy round (okay, that’s an exaggeration but I think you get the point).

Whatever the reason for its popularity is, there is one undeniable fact: it is THE most popular cartridge in world, bar none. Billions of rounds of .22 LR are fired each year, no other cartridge is fired more. In this regard, even something as powerful as the .50 BMG can’t beat this humble little cartridge.

To be fair, the .22 Magnum isn’t necessarily unpopular. It’s not like it’s a wild cat round or anything of the sort — it’s just not as popular as the .22 LR, which also means it will never be as cheap.

22 LR vs. 22 Magnum Pricing Comparison

Now you might be one of the many who think .22 Magnum ammo pricing as just plain highway robbery and depending on your wallet’s status you’re most probably right, but my take on it is, the .22 Magnum is really only too expensive to the point that it has practically zero value proposition when you look at a few things:

- .22 LR bulk ammo is dirt cheap — next to it, any other rifle or handgun caliber ammo (even the cheapest 9mm bulk ammo) look too darn expensive.

- When fired from a rifle, .22 Magnum nips at the heels of standard pressure 9mm in terms of ballistics — and like the .22 LR, standard pressure 9mm ammo is dirt-cheap. Any other cartridge compared to the 9mm (save the .22 LR) looks expensive, no exceptions.

- There are a lot of other cartridges that cost less and yet, are ballistically superior to the .22 Magnum.

Why is 22 Magnum more expensive than 22LR?

The 22 Magnum is more powerful and has a greater velocity than the 22LR, so it is generally more expensive. The 22 Magnum cartridge is also more expensive to manufacture due to its larger size and higher pressure.

Additionally, the 22 Magnum is a more specialized round and is not as widely produced as the 22LR, leading to higher prices.

What’s weird about all this is, from a purely capitalist/manufacturing cost standpoint, .22 Magnum ammo being three to four times more expensive than .22 LR ammo just doesn’t make any sense.

Both rimfire cartridges use brass with a ~24,000 psi SAAMI rating, both don’t need a cup-and-anvil type of primer setup that centerfire cartridges require, and both only use tiny .22-inch diameter bullets that weigh 40 grains or less.

And while it’s somewhat of a common knowledge that the .22 Magnum is far more reliable than the typical .22 LR when it comes to primer ignition, both still use the ancient rimfire design. Both will never be as reliable as centerfire cartridges. Again, this makes the huge difference in price between the two cartridges nonsensical.

22LR is a Better Value Rimfire

The long and short of this section is, if you’re like most of us, i.e. the typical budget-conscious consumer, you’ll find that the .22 Magnum might be appealing but it has nothing on the .22 LR when low prices due to demand and popularity are factored in. What’s the point of having all that energy in a cartridge when you can’t shoot as much of it as you want?

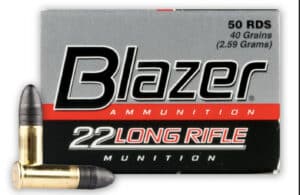

Best 22LR Ammo for the Money

As we mentioned before we think CCI makes the best Rimfiire ammo on the market. Here is our favorite for the money. Especially when you buy in bulk.

| Product Name | Where to Buy | |

|---|---|---|

| CCI Blazer – 22 LR – 40gr | |

| CCI Maxi-Mag – 22 Magnum – 40 Grain |

CCI Blazer – 22 LR – 40gr

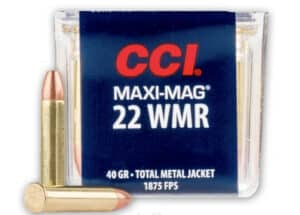

Best 22 Magnum Ammo for the Money

As you may have guessed we don’t think a 22 Magnum is worth the extra expense over the 22LR. However, if you are bound and determined to go with the 22 Magnum, here is our favorite for the money.

CCI Maxi-Mag – 22 Magnum – 40 Grain

Since you’ve looked at both, when looking at the price difference you’ll note ~$.07 vs. $.42 for 22 LR vs. 22 Magnum respectively.

Which is Better – 22 LR vs. 22 Magnum?

This rimfire cartridge showdown is kind of a little biased toward the .22 LR because yours truly is a cheapskate. But looking past ballistics and pricing figures, there can really be only one big differentiator between these .22 rimfire cartridges: that is YOU and what you intend to do with either.

When to choose the 22LR. vs 22 Magnum?

- If all you need are bullets for plinking, .22 LR bulk ammo is the best out of all available handgun and rifle calibers on the market bar none because of its stupid low price.

- If you’re hunting small game and you want to maximize edible meat on all critters you’ll manage to kill, the .22 LR is your best bet.

- If you’re hunting small game and you want to maximize edible meat but you’re trying to do it at longer distances, hyper velocity .22 LR loads like CCI Stingers should give you the controlled destruction you need. Just be aware that there are .22 LR firearms that won’t fire them safely (e.g. Ruger 10/22) so consult your gun’s manual first.

- If you’re into target shooting, the .22 LR is the more accurate of the two — even better, there’s target grade (but crazy expensive) “competition” ammo available for .22 LR firearms.

- If you’re a SHTF prepper, no rig is complete without a rifle chambered in .22 LR. The topic deserves its own write-up so I wouldn’t bother expounding on it, but if you’d like to read more, you can go to this survivalist blogsite. Oh, and don’t even think of buying a rifle in .22 Magnum and loading it with .22 LR cartridges — it won’t work.

When to choose the 22 Magnum vs 22LR. ?

- If you’re hunting up to coyote-size game, the .22 Magnum is way more effective at longer distances — heck there are even reports of people successfully killing deer using it (we don’t recommend it though, especially when there are way more powerful cartridges that guarantee humane kills).

- If you’re in the market for a CCW and you’d prefer to carry the lightest piece without the punishing recoil, the .22 LR and the .22 Magnum are available in a ton of different models — but the .22 Magnum will have better stopping power (personally though, I would recommend going with something chambered in the .380 ACP). And if nothing else, the loud noise (an inherent magnum cartridge characteristic) is a great crime deterrent too.

- If you’re a SHTF prepper, no rig is complete without a rifle chambered in .22 LR. The topic deserves its own write-up so I wouldn’t bother expounding on it, but if you’d like to read more, you can go to this survivalist blogsite. Oh, and don’t even think of buying a rifle in .22 Magnum and loading it with .22 LR cartridges — it won’t work.

22 LR vs. 22 Magnum – Conclusion

This comparison was one of the hardest I’ve done in a while. On the one hand, the .22 Magnum is the pinnacle of power and innovation in .22-caliber rimfire cartridges, a true masterpiece that has withstood the test of time — but ironically, one that has yet to escape the shadow cast on it by the very thing it attempted to supersede.

One the other, the .22 LR, one of the earliest self-contained metallic cartridges that can now be considered a relic that is more than a century old, continues to become the most popular cartridge in the world with its solid reputation for accuracy, versatility and affordability — despite its flaws and weaknesses.

If it were only a simple matter of comparing bullet velocities and muzzle energies. Then the .22 Magnum would have won hands down. But like most things in life, caliber comparisons are never going to be easy. So after careful analysis, we’re happy to conclude that all things considered, the .22 LR wins this showdown.

Recommended Reading

Ultimate Guide to Bullets, Calibers and Cartridges